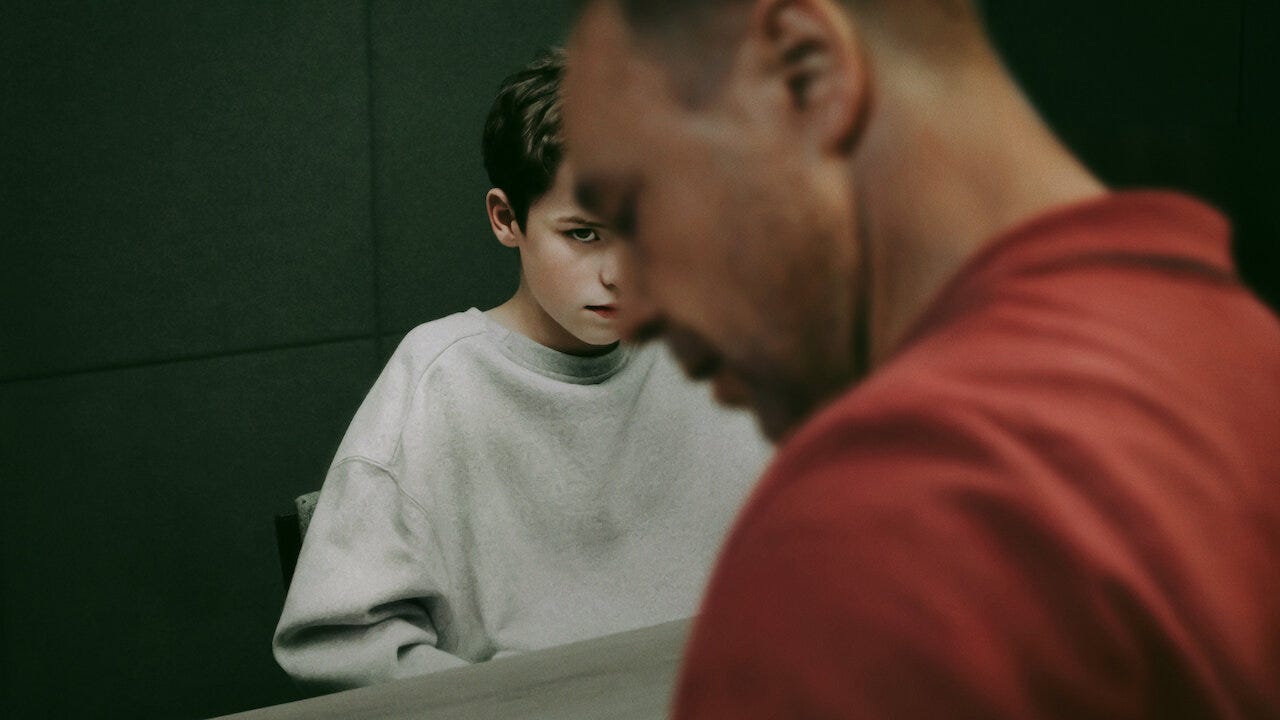

Along with seemingly everybody else I’ve recently been watching the Netflix series Adolescence. It is a striking film that is masterfully shot and powerfully acted. It has also generated a worthwhile public conversation. Much of this conversation has been constructive; however some of it has been animated by a desire to change the subject - to talk about anything but misogyny and the radicalisation of young men on the internet.

I found Adolescence surreal to watch at times. Since 2018 I have been researching the so-called ‘manosphere’ - a loosely affiliated network of masculinist websites, blogs and online forums. The fruit of my labour, Lost Boys: A Personal Journey Through the Manosphere, is out with Atlantic on 5 June. In normal circumstances a book like this would not have taken so unfathomably long to write. But the years since 2018 have been highly abnormal. First the pandemic meant that I couldn’t travel. Then, almost as soon as that was over, my grandmother (whom I was extremely close to) died. Perhaps not surprisingly, I had little desire to re-immerse myself in a culture that got its kicks diminishing women while I was still grieving for the one I loved.

Because it took so long to finish, much of the writing took place under a cloud of uncertainty. I wondered whether the subject matter would be old news by the time the book came out. Back in 2018 there was a lot of interest in incels (involuntary celibates) and Jordan Peterson. By 2022 Andrew Tate was all the rage. I was sure that by 2025 the hyper-masculinity stuff was going to peter out. And then Donald Trump was re-elected and Mark Zuckerberg went on the Joe Rogan Experience to preen about ‘masculine energy’. Adolescence, a film about the radicalisation of a young boy by the manosphere, is now Netflix’s top show globally.

Today I feel a bit like a funeral director in the aftermath of a mass casualty event. I would have preferred things to have turned out differently, but considering they haven’t, I intend to put my knowledge to some practical use. Having spent so much time researching the manosphere - including interviewing and interacting with hundreds of men and spending months at a time embedded on a course which purportedly taught men how to become ‘high status alpha males’ - I feel as if I have something worthwhile to contribute.

It is in the nature of television to over-dramatise things and Adolescence depicts an extreme sequence of events. Murders inspired by the manosphere are mercifully rare (I go over several of them in detail in the book). Yet for every act of extreme violence there are probably countless instances of abuse and coercion that are given moral license by the subculture’s misogynistic doctrines. Indeed, many unpleasant things follow from the proposition that women are not quite fully human, even if some of our professional anti-alarmists would like to wave this conversation away as a ‘moral panic’.

Much of the debate inspired by Adolescence has focused on fatherlessness. It is an interesting jumping off point and conservative hand-wringing about the subject is not without foundation. Yet absent fathers are better than violent ones. Moreover, fatherless homes are sometimes a byproduct of the fact that women nowadays feel less coerced into ‘making it work’ with abusive men.

Anti-feminist backlash can bring to mind a line from It Can’t Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis’s dystopian novel that enjoyed a resurgence during the first Trump administration. ‘Every man is a king so long as he has someone to look down on,’ wrote the author. As women have thrown off some of the oppressive strictures of the past and entered the labour force as (at least in theory) equal participants, some men have experienced a relative loss of status. Until fairly recently, men who found themselves cowed at work could at least dominate their families in the home. They still can in places like Russia, where a woman is killed by a man in a domestic setting every forty minutes. Vladimir Putin knows he has little to offer Russia’s menfolk besides poverty and war. And so he endows them with a sense of domiciliary lordship and dominion. In 2017 the Russian leader signed a law that partially decriminalised domestic violence.

It wasn’t so long ago in the West that women were treated as a form of property and divided up accordingly. Nowadays they mostly get to choose for themselves and the manosphere is rightly seen as a bilious wail of resentment at the fact.

Yet the ‘backlash’ thesis only takes us so far. The rise of the manosphere should probably also be seen as a morbid symptom of the suffusion of market logic into every aspect of life. As is often the case, the clue is in the language. Masculinity gurus refer to a ‘sexual marketplace’ where to succeed men must embody certain characteristics that (coincidentally) also correspond with being the ideal neoliberal subject. Dominance, status, and crippling levels of productivity render a man ‘high value’ (people are frequently made to sound like Ebay collectibles) and audiences of impressionable men are encouraged to view life entirely through the prism of getting rich. Women on the other hand are treated either as ornamental status objects - one of the spoils for a successful performance of masculinity - or as breeding stock for patriarchs.

Jamie, the teenage boy who murders a girl from his school in Adolescence, mentions something called the ‘80/20’ rule. ‘80 per cent of women are attracted to 20 per cent of men. You must trick them, because you’ll never get them in a normal way,’ the 13-year-old protagonist tells his psychologist. In its garden variety self-help guise, the 80/20 rule (sometimes called the Pareto Principle) is one of those sterile maxims whose spiritual home is the jejune world of LinkedIn. The basic idea of this supposed ‘law’ is that 80 per cent of consequences come from 20 per cent of causes. The manosphere transposes the same template to sex and relationships. According to Jordan Peterson, sexual access for males is a ‘Pareto-distributed phenomena where a small proportion of the males get most of the invitations’. During the immersive part of my research, I heard one guru explain it as follows to a group of students who had signed up for his $10,000 ‘alpha male’ course (yes, really):

As we got into monogamous societies, what happened was low-status men got at least one girl that they could have sex with. Then after birth control and the sexual revolution we allowed people to choose more, and what women were choosing was the high-status men, so these men at the bottom became surplus again. That’s why you guys are here.

In other words, women are choosing a small percentage of ‘elite’ men and condemning a flotsam of sexual no-hopers (the 80 per cent) to the status of surplus men. This sort of rhetoric is usually accompanied by claims that western civilisation is going down the tubes because society no longer places restrictions on female sexuality (‘culturally enforced monogamy’, as Peterson has euphemistically called it).

In reality the 80/20 rule is a conspiracy theory that doesn’t stand up even in the world of dating apps. According to a study of user activity on Tinder, while women on the app tend to rate men more poorly in terms of their looks, they are also more likely to message the poorly rated men. By contrast, men tend to rate women better in terms of looks, but a majority are only messaging the most popular third of women.

And yet the 80/20 rule (and the manosphere itself) started to gain traction around the time that image and video-based social media took off. Instagram was launched in 2012; ten years later it would be home to a billion users – around an eighth of the world’s population. Tinder, a place where people are depicted as two-dimensional objects in a catalogue of flesh, launched in the same year. These platforms in particular have helped to distort ideas around what is normal and accepted. The more beauty and abundance on one side of the screen, the greater the sense of material and spiritual impoverishment on the other. We know that social media makes women feel insecure about their bodies; yet the same thing is increasingly true for men. A 2025 study published in Psychology of Men & Masculinities found that adolescent boys were increasingly using anabolic steroids to achieve the muscular physiques idealised on social media. If nobody feels like they are good enough anymore then perhaps it is because we are not supposed to.

Which makes it easier to convince young men that they lack the requisite qualities to succeed in the so-called sexual marketplace. In the analog age masculinity hucksters were forced to place their ads in the back of top shelf magazines. Thanks to social media, where the illusion of success is indistinguishable from the real thing, their bombastic heirs can enchant young men with telegenic charisma and portrayals of a luxurious lifestyle (in common with other pyramid schemes, the trappings of wealth are usually dependent on the guru’s ability to extract money from his followers).

This is why the wisdom of putting smartphones in the hands of children is so central to the debate around the manosphere. We tend to explain radicalisation by searching for pre-existing vulnerabilities. This is often the most appropriate approach: radicalisation can feed on inner turmoil and insecurity. Yet such feelings are not always organic: the market can play its own role in their generation. Wealth in a capitalist economy is accumulated through the creation of needs as much as their satisfaction. And smartphones are the vehicle through which masculinity entrepreneurs are able to circumvent other forms of socialisation (parents, teachers, approved role models) in order to cultivate their pied piper-like appeal.

When I was at school being ‘cool’ was synonymous with possessing whatever action figure or clothing brand or skateboard the market had convinced you was essential. What makes smartphones different is that the commodity itself is the beginning rather than the end of the story. ‘We look through them into the infosphere,’ as the philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes in Non-things. Venturing into the ‘infosphere’ these days increasingly summons feelings of browsing a sales catalogue of low repute. Search engines try to pull you away from the things you are searching for; social media generates conflict and atomisation; dating apps get rich from perpetual singledom.

And this is the respectable face of the internet. It is easy enough to find oneself in the slipstream of even worse sales funnels1. Charismatic masculinity influencers reel young men in by hammering away at their insecurities. They then present themselves as saviours and guides. The sales pitch goes something like this: ‘The rules of the game have changed; someone like you will never get a girlfriend; however if you follow me (and buy my course which is $495 for a limited time only) I will show you how to escape the ‘Matrix’ (i.e. by embracing a rigid and cartoonish coda of masculinity).

To be online in 2025 is to be one-step removed from the subterranean world of masculinity demagogues. Adults are free to navigate these waters at their own peril. But I suspect that as a society we will come to regret giving children untrammelled access to the devices through which these toxic Confidence Men can peddle their wares. After all, there are more important things in life than the assimilation of kids into the smartphone market.

Lost Boys is currently available to pre-order.

Banning influencers from social media platforms merely leads to their content appearing elsewhere: Andrew Tate’s videos are easily accessible on Rumble.