Orwell, the author who ‘quarried his way down into the heart of the human condition’

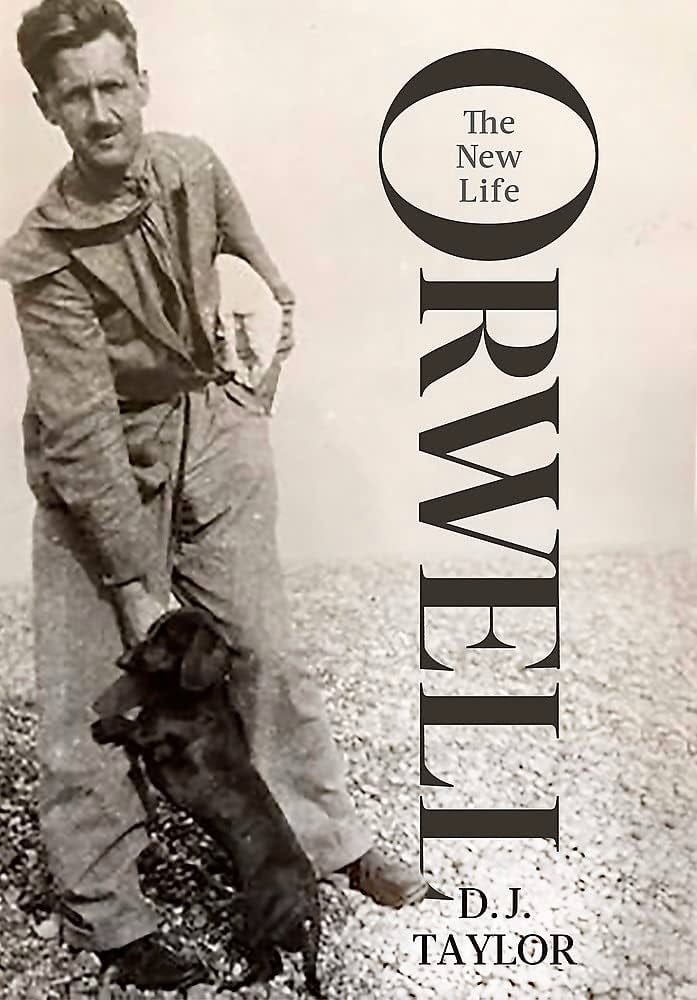

Book Review: Orwell: The New Life by D.J. Taylor

One of the marvellous things about reading George Orwell is the feeling one gets that he is writing directly for you. The matter-of-fact Swiftian style (observable especially in later works) is part of it, but so too is the character that jumps out at you from the page. Orwell constantly reassures you - the reader - that he is just like you; that he is fallible and not an intellectual; and that he is persuading himself first and foremost. As Richard Filloy once noted in a study of Orwell’s rhetoric, ‘Orwell persuaded not on the strength of an exceptional personality but on the ordinariness of a commonplace one’.

If this seems like a sleight of hand (which it most certainly is: Orwell was an intellectual) it is one that most of us can readily forgive. We forgive because there is something else that shines through the plain-speaking prose, something that shares a great deal in common with the ‘generous anger’ that Orwell once attributed to Charles Dickens. When imagining the face of the nineteenth century author ‘somewhere behind the page’, Orwell might have been writing about his own face

‘…the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry - in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.’

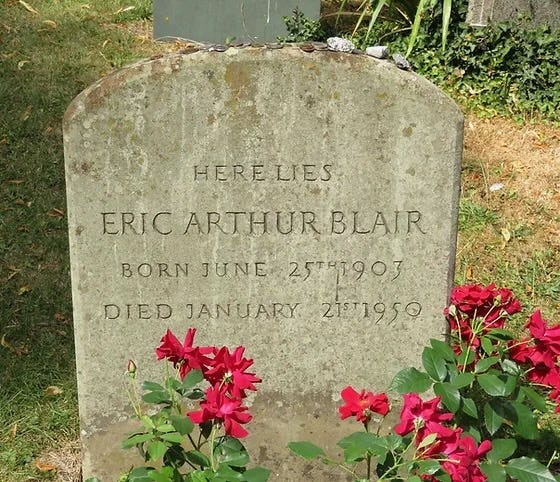

Upwards of 70 years after he died of pulmonary tuberculosis aged just 46, George Orwell seems ‘more important than ever’ according to D.J. Taylor, the author of a new biography of the writer born Eric Arthur Blair. Having produced the acclaimed biography Orwell: The Life in 2003, D.J. Taylor has written an updated version, Orwell: The New Life, which, two decades on from the original, builds on the first with information gleaned from a cache of ‘hitherto unknown letters’.

Having discovered a copy of A Clergyman’s Daughter on his parent’s bookshelves aged 13 - a book that Orwell would later disown as a failed experiment - Taylor, like so many others, swiftly adopted Orwell as ‘my writer’. ‘To read him and write about him,’ Taylor says, ‘is one of the greatest satisfactions I know’.

No known recordings of Orwell’s voice exist; yet his prodigious authorial output - Taylor estimates that Orwell produced over two million words in a writing career of a little over two decades: enough to fill an area roughly the size of Norwich city centre - remains both a source of pleasure and a terrifying augury of the way in which individual liberty is constantly at risk of being crushed under Nineteen Eighty-Four’s famous ‘boot stamping on a human face’.

****

The continued salience of Orwell undoubtedly has something to do with the fact that the three great twentieth-century questions of fascism, Stalinism and empire - the questions which Orwell was essentially right about - are still being played out, even if today they take on a slightly different configuration. Who can look on at the Russian invasion of Ukraine, or at China, the world’s first digital totalitarian state - or at a resurgent Neo-Fascism in the West - and not be tempted to reach for the ‘wintry conscience’ - a title bestowed on Orwell by VS Pritchett - and his obstinate willingness to face unpleasant facts?

It was as the storm clouds gathered overhead in the 1930s that Orwell truly got going as a writer. That ‘low dishonest decade’ - as W.H. Auden called it - was characterised by a widespread perception of an inevitable slide to war. ‘Year after year there were discordant voices predicting conflict at any time,’ writes the historian Richard Overy in The Morbid Age, his study of the gloomy interlude between the wars. Orwell’s first book, Down and Out in Paris and London - an autobiographical account of tramping and working as a scullion - was published in 1933, the year Hitler came to power. (The seedy and unwholesome material contained in the book encouraged Blair to adopt a pseudonym so as not to scandalise his shabby-genteel parents.) A later novel, Coming Up for Air (1939), anticipated the destruction wrought by the air-raids of Hitler’s bombers.

Burmese Days, Orwell’s first novel - which appeared a year after Down and Out - was an examination of the debasing effect of ‘the dirty work of empire’ [Orwell’s words] on both ruler and subject, conceived in the years after Orwell had quit his job as a policeman in the colonial service. Two fairly mediocre novels followed - A Clergyman’s Daughter and Keep the Aspidistra Flying - before Orwell was given £50 by the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz to undertake a two-month excursion to the north of England to investigate the conditions of working class communities.

The book that resulted from this voyage of discovery - The Road to Wigan Pier - is a disjoined affair, the first half a gripping anthropological study of poverty and squalor in the industrial north - ‘a frightful landscape of slag-heaps and belching chimneys’ - the second a polemic in which Socialists are excoriated for being cranks and oddballs. ‘One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words “Socialism” and “Communism” draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, “Nature Cure” quack, pacifist, and feminist in England,’ writes Orwell.

‘From an early stage in his literary career, almost as far back as the first tramping journeys, Orwell was determined to identity with the working classes,’ writes Taylor. This esteem for victims of the class system was on full display during the time he spent among the miners while researching The Road to Wigan Pier. Orwell describes the men down the pit as looking like ‘iron hammered iron statues’. Yet while he turned a sharp eye on the destitution he encountered, Orwell’s failing was to show scant interest in the popular working class entertainments of the day. According to his brother-in-law Humphrey Dakin, Orwell avoided any social situations in which the working classes could be seen enjoying themselves. Elsewhere, Orwell attended a British Union of Fascists rally, from which he came away depressed at how easily a working-class audience was ‘bamboozled’ by the rhetoric of Oswald Mosley.

Orwell was not alone in writing a ‘state of England’ book during this period. Gollancz had published J.B. Priestley’s English Journey in 1934. Meanwhile John Newsome’s Out of the Pit: A Challenge to the Comfortable came out in 1936, the same year Orwell set out for Wigan. It was a commonplace in the 1930s that free-market capitalism no longer worked. One of the most successful novels of the decade - the working class writer Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole - seemed to relay this failure of capitalism to satisfy the basic wants of millions of working people. The book was published in June 1933; in January of that year the unemployment rate had risen to 2.5 million, or 25 per cent of the workforce.

And yet it wasn’t until he went to Spain that Orwell would become a committed Socialist. At the end of 1936, having finished the manuscript of The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell left the austere and poky Hertfordshire cottage he had been renting with his new wife Eileen O’Shaughnessy and set out, via France, for Spain, where General Franco’s military mutiny - supported by the Catholic Church and the aristocracy - was attempting to restore feudalism. In one of Orwell’s great symbolic gestures, he pawned the family silver to fund his travel costs.

Arriving in revolutionary Barcelona in December 1936, Taylor describes Orwell as ‘transfixed’ and ‘captivated by the fervour he saw around him’. As Orwell put it in Homage to Catalonia, ‘Human beings were trying to behave as human beings and not as cogs in the capitalist machine’. The experience left ‘an inalienable mark’ [Taylor’s words] on Orwell thereafter; or as Orwell put it, here was a situation where the ‘working class were in the saddle’ and ‘a state of affairs worth fighting for’. Shortly before he returned to England, Orwell would write to his old friend Cyril Connolly to say that he has seen great things ‘& at last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before’.

From Barcelona Orwell travelled to the Aragon Front where - armed with a forty-year-old German Mauser - the atmosphere was languorous and feculent. As Taylor writes, ‘the need to keep warm took precedence over anything that might be happening on the Fascist lines’. Orwell would describe his time at the front as a comic opera war where people occasionally got killed. He did eventually see some action: he took a sniper’s bullet through the neck - a bullet which, had Orwell been a few centimetres shorter (he was 6ft 2in tall) would have cut through his carotid artery and killed him.

As well as turning him into a convinced Socialist, it was in Spain that Orwell witnessed at first hand the malign influence of the Soviet Union under Stalin. A Stalinist purge of the POUM - the Trotskyist militia that Orwell served in during his time in Spain - occurred during the first two weeks of May 1937. The POUM were depicted by the Communist press as ‘agents of Fascism’ who were in the pay of Franco. Orwell was particularly enraged by a cartoon depicting a mask emblazoned with a hammer and sickle slipping from a face to reveal a swastika beneath it. This was his ‘first introduction to the workings of a totalitarian state’, writes Taylor. A decade later Orwell would reflect that ‘Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.’

****

Rather than being a sage or a prophet, Orwell was politically inconsistent and many of his predictions failed to materialise. Indeed, it is possible to quote the Orwell of the 1940s against the Orwell of the 1930s and vice versa. Orwell struck an ultra-left position for much of the 1930s, dismissing Hitlerism as no worse than British jingoism. He believed that fascism was merely capitalism in extremis and that ‘war against a foreign country only happens when the moneyed classes think they are going to profit from it’. A short time later, citing a dream he had had on the eve of the Russo-German Pact, Orwell came out as a passionate supporter of the war. ‘There is no real alternative between resisting Hitler and surrendering to him, and from a Socialist point of view, I should say that it is better to resist,’ he wrote in ‘My Country Right or Left’ (1940). Soon after he would be deriding those who took the anti-war position - a position he had taken himself for much of the preceding decade - as ‘objectively pro-Fascist’.

If Orwell at times appears as a bundle of contradictions, it is this aspect of his personality that allows intellectuals of all stripes - Socialists, Neoconservatives, traditionalists - to posthumously stake a claim to him. He was a self-described ‘tory anarchist’ who hoped to see red militias billeted in the Ritz; a Socialist who put his adopted son Richard down for Eton; an internationalist who carved out a particularist definition of Englishness; and an avowed atheist who left directions that he should be buried according to the rites of the Church of England.

If Orwell’s early tramping expeditions were conducted on the basis of [as Taylor] writes ‘a series of deep-rooted psychological hang-ups that he [Orwell] burned to subdue’, it’s similarly true that Orwell spent much of his adult life ‘taking his own temperature’, as the late Christopher Hitchens observed. As a young man Orwell was demonstrably antisemitic. In his early works Jews are nearly always portrayed in a negative light. But as he began to interrogate his own prejudices, Orwell noted that the ‘starting point’ for any investigation into antisemitism should not be, ‘Why does this obviously irrational belief appeal to other people?’ but, ‘Why does antisemitism appeal to me?’ Reviewing The Iron Heel by Jack London in 1940 - a book depicting an oligarchal tyranny that uses terror to ward off Socialism - Orwell argues that London could understand Fascism better than most Marxist Socialists (whose thinking was overly mechanistic) because he had a ‘Fascist strain’ in himself. You suspect the same was true of Orwell, who understood the appeal of totalitarianism due to his own authoritarian streak.

Various literary contrarians have attempted to demolish Orwell’s reputation as a moral authority over the years. Conor Cruise O’Brien described the four-volume Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell (1968) as ‘a contribution to a cult’. For Scott Lucas in The Betrayal of Dissent (2004), Orwell is ‘policeman of the left’ who was a member of the conservative camp all along. Plus ça change etc., today’s young literary men are still haughtily sounding off about Orwell: he is apparently ‘fraudulent’ whereas there is ‘nothing special’ about his prose. Elsewhere, yelling out from behind their trestle tables are what Taylor calls ‘the tiny handful of Stalinists who have never forgiven him for Animal Farm’s burlesque of the Soviet Revolution’.

Orwell of course has his ever-present crowd of admirers - many of whom appear to know little about the author beyond a few bastardised quotes from Nineteen Eighty-Four. Yet it has become almost a right of passage for cynics to give the old man’s reputation a kicking. Which is perhaps fair enough: it was Orwell who wrote (in an essay on Gandhi) that saints should always be judged guilty until they are proven innocent. Yet the incessant need to despatch every sacred cow into this abattoir of world-weary disbelief often disguises what Orwell would probably have called a ‘blimpish’ outlook. If even Orwell - who Taylor rightly says has ‘quarried his way down into the heart of the human condition’ - is just another fraud and poser, then perhaps his egalitarian sentiments are bunkum too.

Yet it is Orwell who endures, while the typical surly critic who takes aim at him resembles ‘a small child trying to bring down an elephant with a pea-shooter’, as Taylor writes. Unlike many of his well-bred Etonian contemporaries, Orwell remained poor for most of his life. It was only with the publication of Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) that he began to be comfortably off. ‘I’ve made all this money and now I’m going to die,’ he said to Denzil Jacobs, a member of Orwell’s Home Guard section, a few weeks before he actually did die in University College Hospital, London.

Orwell: The New Life should be the last word when it comes to Orwell studies; and yet it is far from a starry-eyed account of the author, even if Taylor admits that Orwell is his ‘guide, enthusiast and mentor’. To be sure, Taylor acknowledges that Orwell went around ‘propagating his own myth’. He also notes that, like lots of other ‘Great Men’, Orwell owes an unacknowledged debt to the women in his life - women such as his benevolent Aunt Nellie and his first wife Eileen. It is Eileen - a bright and capable partner willing to set aside her own ambitions in order to fulfil the role of a complaisant ‘muse-cum-secretary’ - who keeps home for the abstracted and otherworldly Orwell; meanwhile he pursues other women behind her back.

And yet the notes of reproval from contemporaries that invariably crop up in the book are vastly outweighed by the testimonies of others who remark on Orwell’s ingenuousness, his gentleness, his love of nature and children and animals, as well as his innate political decency. As Taylor writes, ‘fans who wrote to him invariably got replies; aspiring writers who had petitioned him received courteous letters of encouragement; editors of small circulation magazines who asked for contributions frequently struck lucky.’

Even if Orwell did employ certain affectations to disguise his gentlemanly origins - the moth-eaten blazers, the cheap and foul-smelling tobacco, his Duke of Windsor cockney or the liking he feigned for margarine and strong tea - a genuine esteem for the working classes shines through, and he remained a self-proclaimed democratic Socialist until the end of his life. Travelling in a car on the way to Orwell’s funeral in the bitterly cold January of 1950, the Observer editor David Astor asked his sister Avril who her brother had most admired. ‘The working-class mother of eight children,’ she replied.

Excellent review, thank you. I read the previous edition and maybe will have to get around to this one at some point.

Wonderful piece. I will look forward to reading Taylor's work.