The meaning of Russell Brand

A disgraced comedian, media arse-covering and the revolt of the half-educated

Back in 2013 I described the weird veneration by some progressives of the comedian Russell Brand as follows:

‘a comedian who won fame by sexually humiliating a woman on the radio and who apparently thinks it normal to harass every woman in his vicinity is now Che Guevara because he uses words like ‘pre-existing paradigm’ in conversation with Jeremy Paxman.’

I bring this up not to say I told you so but because we are currently being told that Russell Brand is entirely a product of a wider misogynistic culture, and that his success, public prominence and (potential) crimes are nothing to do with the individuals (i.e. journalists and politicians) who indulged and enabled him over the years.

And indulge him they did. The noughties culture in which Russell Brand rose to prominence was certainly grim - sleazy magazines such as Nuts and Zoo, Little Britain with its poor-baiting, a preponderance of Oxbridge-educated men pretending to be working class. But it’s too convenient to outsource blame for Russell Brand entirely to ‘the culture’, which is a synonym for everyone, which can easily become a synonym for no-one.

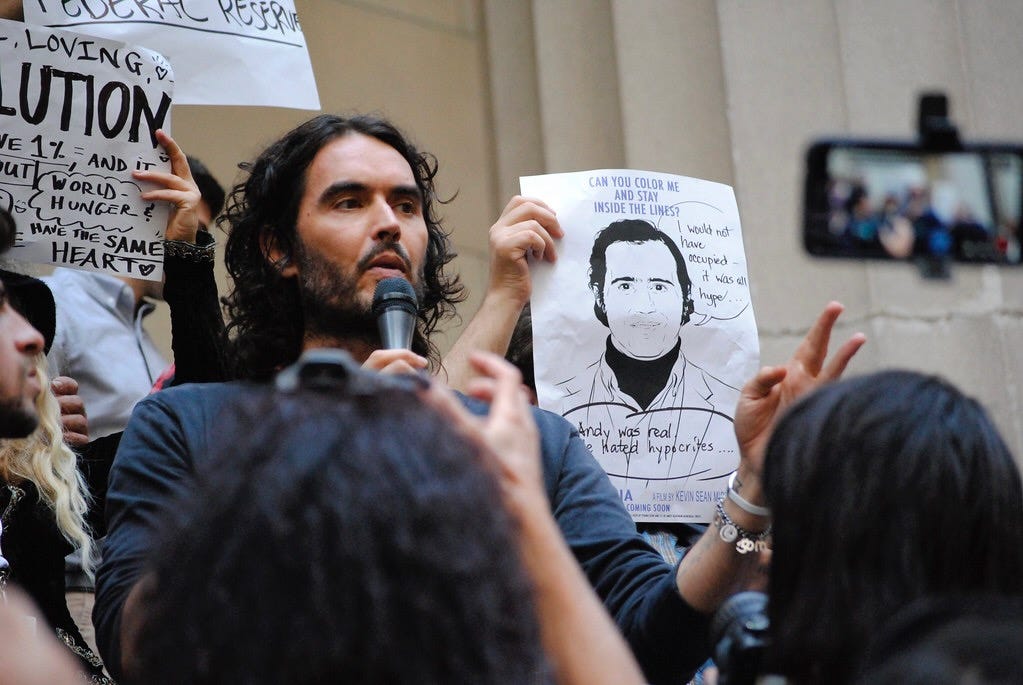

When I wrote that article back in 2013 Russell Brand was being feted by influential people as some sort of revolutionary messiah. He was invited onto current affairs programmes such as Newsnight and Question Time, was brought before a Home Affairs select committee, guest edited the New Statesman and attended editorial meetings at the Guardian. In 2014 Brand took to the stage with the left-wing journalist Owen Jones, who he described as ‘our generation’s Orwell’ (Jones was at that time writing leaden agitprop for the dictatorship in Venezuela, which made the comparison even more grating); the Labour leader Ed Miliband also appeared on Brand’s podcast The Trews.

In 2013, a year prior to Brand’s reinvention as a cockney Oscar Wilde, the comedian’s ex-wife the pop star Katy Perry had described him as ‘very controlling’. Prior to that, in 2006, another pop star, Dannii Minogue, had called Brand a ‘vile predator’ who ‘wouldn’t take no for an answer’.

As well as puffing Jones’s book The Establishment, whose jacket blurb echoed the conspiratorial tone Brand would embrace wholeheartedly a few years later - ‘Behind our democracy lurks a powerful but unaccountable network of people’ - one of Brand’s endorsements was splashed across another book: The Rules of the Game, a pickup artist manual by the journalist Neil Strauss. The book was a follow-up to The Game, Strauss’s bestselling account of his time immersed in the seduction community. The sequel was an attempt by Strauss to cash in on the success of The Game by revealing some of the coveted pickup techniques he had used so successfully on women to a libidinous male audience. Strauss even admitted that some of what was contained in the book might be problematic. ‘So is this material manipulative? Of course it is,’ Strauss boasted. ‘Every great romantic comedy begins with some sort of manipulation.’ The important this was that the techniques worked, and a jacket blurb by Brand was intended to convey that they did. ‘Neil Strauss’s writing turned me from a desperate wallflower into a wallflower who can talk women into sex,’ wrote the comedian.

Brand’s attitude towards women was right there in plain sight. But as Orwell had once put it, to see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle. Following Brand’s ‘revolutionary’ turn, various media luvvies and back scratchers seemed to get taken in. Because he echoed their ideological obsessions; because they wanted some of his celebrity stardust to rub off on them; because they grasped that internet guru-dom was going to be the next big thing.

At the time Brand struck me as a morbid symptom of the era in which we lived. Emancipatory mass movements no longer existed in any meaningful sense; and so instead people began to look to charismatic individuals for salvation. The student protest movements had fizzled out and Britain was ruled by a clique of former Etonians who were busy demolishing the state. A crackpot posing as a genius always has a certain chance of being believed, as Hannah Arendt once noted; and Brand seemed to cast a spell over political audiences hungering for a glimmer of hope at a fairly bleak time. ‘His energy is totally infectious,’ cooed the Guardian.

Brand’s formula as a charismatic guru involved a display of unshakeable, gleaming-eyed conviction tempered with stylised vulnerability. ‘Don’t get distracted and deluded by your selfish nature!,’ he told an audience in Westminster during a Guardian Live event with Owen Jones in 2014. Today, with the comedian facing multiple allegations of rape, sexual assault and emotional abuse - claims that Brand emphatically denies - this sounds a bit like projection. Later on in the same show Brand would expand further on his own insatiable desires: ‘I want attention. I want women. I want drugs. I want food. I want, I want, I want. I exemplify the problems of our culture . . . I’m a viciously authoritative, controlling man.’

Here’s to taking people at their word when they tell you who they really are.

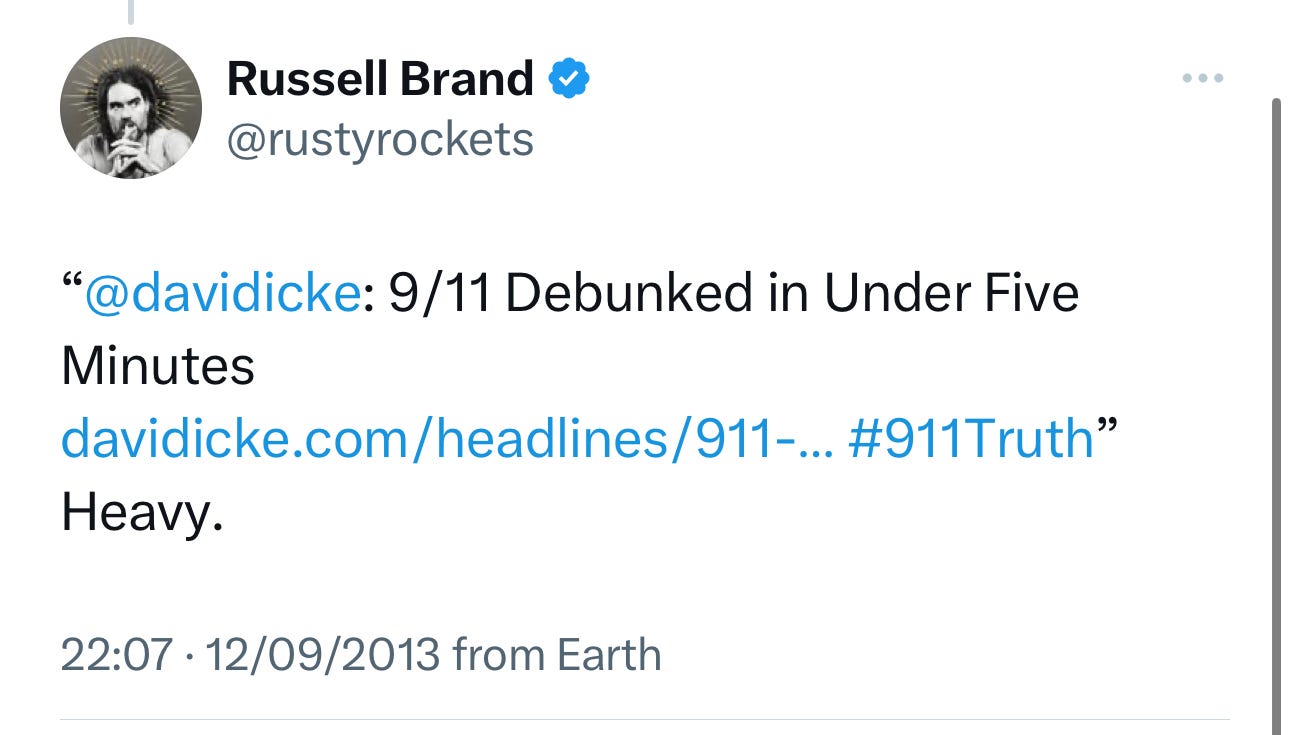

The Covid-19 pandemic caused a form of epistomological breakdown in many people. They emerged from lockdown as if brushed by madness. I suspect this was partly a result of the extra time people were spending. Out of genuine conviction or acquisitive opportunism - perhaps a mixture of both - Brand used the time to reinvent himself as a right-wing conspiracy theorist. In doing so he discovered a large constituency of people who (to paraphrase Arendt again) were ready at all times to believe the worst, no mater how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because they held every statement to be a lie anyhow. From a converted pub in Henley-on-Thames, Brand pumped out a torrent of conspiracy-laden content on topics such as the Covid vaccine (‘how can we really continue to just “trust the science”?’), global warming and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Such potent blends of cynicism and credulity have become financially lucrative in recent years: income from Brand’s YouTube channel alone (he also broadcasts on Rumble) grew from $750,000 in 2019 to $4 million in 2023. Yet I don’t believe that money alone explains Brand’s conspiratorial worldview. I think he’s always been a crank. He was simply given a free pass at one time because his ranting chimed with fashionable opinion.

I spent the pandemic cooped up in a small town in Somerset shielding my grandmother. As things began to open up, I began to encounter more and more people - in the pub, at the gym, among family friends - who were being influenced by conspiracies they were consuming online. Brand’s name came up on multiple occasions.

This is not to say that such people don’t exist in London - obviously they do - but I always seem to encounter more of them when I am visiting family in the provinces.

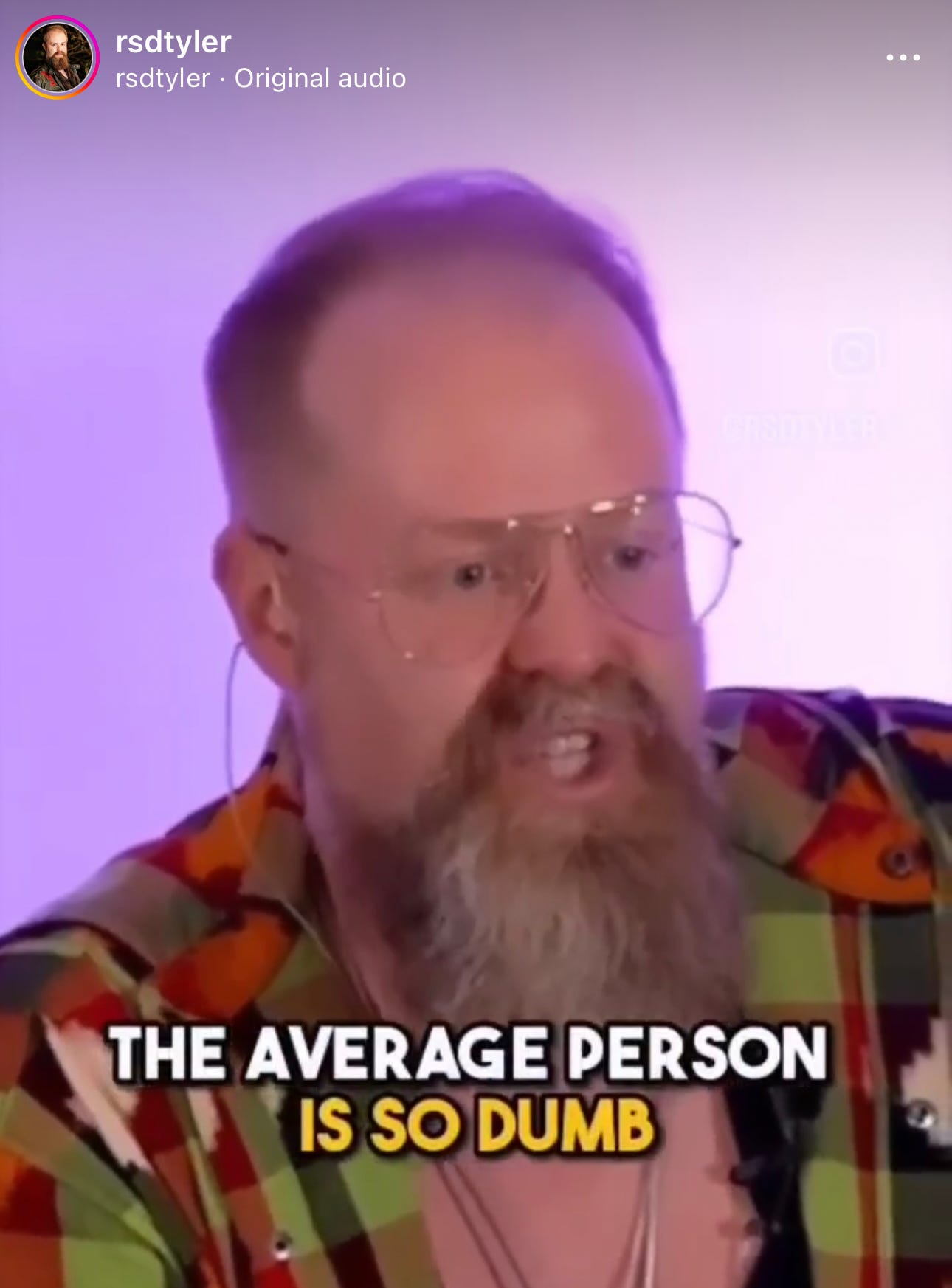

A sense of thwarted potential is fertile ground for conspiracy theories. The philosopher Eric Hoffer has suggested that those who become possessed by exciting ideas are frequently ‘selfish people who were forced by innate shortcomings or external circumstances to lose faith in their own selves’. This sounds like a condescending thing to say, but as a lower middle class autodidact myself I feel permitted to make the observation that conspiracy culture often resembles a revolt of the half-educated. There are probably millions of people in Britain whose intellectual pretensions have been thwarted by their social origins. Therefore a supercilious elitism - the notion that they have access to some ‘truth’ that you and the other normies don’t have - may function as a psychological palliative for internal feelings of inferiority.

Others who seem susceptible to conspiracies are those who have achieved modest success in business and wonder why that esteem generated is not reflected back at them elsewhere. They have made a bit of money and, because that is often quite difficult, they view themselves as experts in everything (society frequently promotes the idea that ascent in business represents the ultimate form of personal triumph, which is why we have public figures like Donald Trump and Elon Musk). Meanwhile, those who occupy the intellectual commanding heights in our society - academia and the media - often look down their noses at this haughty merchant class. Indeed, there are few people the intelligentsia loathe more than those with a predilection for selling things. And so members of this merchant class begin to chafe at the ‘establishment’ and a ‘legacy media’ which sometimes views them with distain. Gradually, everything they believe about the world comes to be framed in opposition to the mainstream. They begin to think of themselves as an alternative intellectual elite.

I am opening myself up to criticism by typecasting people like this. By affixing condescending labels - ‘midwits’, ‘pseuds’, purveyors of ‘deepities’ - to the creators and consumers of independent media, one can sound as if one is saying that only privately educated leader writers for the Times should be allowed to expound on the state of the world.

In the aftermath of the 2016 Brexit vote there was a lot of faux concern swilling around about the ‘left behind’ classes and how they were being sneered at by ‘metropolitan liberal elites’. Such arguments were frequently deployed by grifters and charlatans who feigned a pugnacious plain-man’s dislike of ‘intellectuals’. And yet, the conception of an elitist media class is not without merit. There is a fatuous and self-satisfied counterargument to the conspiratorial complaints heard in the alternative media space which says, effectively, that people have ‘never had it so good’. In other words, individuals are searching for saviours and gurus for no reason other than their own stupidity and selfishness. This attitude comes across in a piece by Will Lloyd published recently in the Times:

Brand is only right about one thing. He really does exemplify the problems of our culture. On the same day the allegations against him were published, polling found that a third of British adults “regard the system as broken and are highly suspicious of those they hold responsible”. A similar poll in January found that 38 per cent of the British population agrees with the statement: ‘The world is controlled by a secretive elite.’ This is Russell Brand’s Britain.

Endless excuses are made for that nation. If only they were not manipulated by social media companies. If only their manufacturing jobs hadn’t been obliterated. If only the elites had managed the fallout from the financial crisis better. These excuses treat this demos like a succession of media managers seem to have treated Brand — as a difficult and helpless child who needs to be abetted and soothed. Everything is somebody else’s fault. A blind eye is always turned.

Passages like this simply won’t do. When people are losing their homes because of high interest rates; when families are unable to see a doctor; when inner cities are rapidly turning into cardboard slums and tent cities; when the utility companies that provide water and energy are treated as cash cows for shareholders while prices go up - are we really reduced to blaming everything on personal responsibility? I suppose it is inevitable that privately educated columnists for the Times should try to reassure themselves that this is so. But I see no reason why people who are angry about the current state of things should feel embarrassed for their occasional lapses into commitment.

The rage of individuals such as Russell Brand, Tucker Carlson and Andrew Tate may resemble the anger of a disappointed child. For Tate specifically, it is obvious that ‘the Matrix’ is simply a synonym for any form of authority or restraint that is placed upon his own rampant and selfish individualism.

But if the world we live in is favourable to grifters, I suspect this is partly because institutional vehicles for rebellion hardly exist. ‘When there’s no worthwhile banner, you start to march behind worthless ones,’ as Victor Serge once wrote. ‘When you don’t have the genuine article, you live with the counterfeit.’

And so it is with Brand and the other gurus, messiahs and therapists currently being foisted upon us.

Great piece of writing👏

Great article! One of the better I've seen on Brand.